The great-grandfather of Erica Clark Kenny was Edward Clarck. He was of French background and his family was from St. Pierre and Miquelon - perhaps born there in 1895.

These islands are in the Gulf of the St. Lawrence River, relatively close to Newfoundland (about 800 miles NE of Boston. Though part of North America, they remain territorial possessions of France - the only overseas colonical possessions of France, today.

Today, both Saint-Pierre & Miquelon are modern, quaint French towns and the most original destination in all of North America.

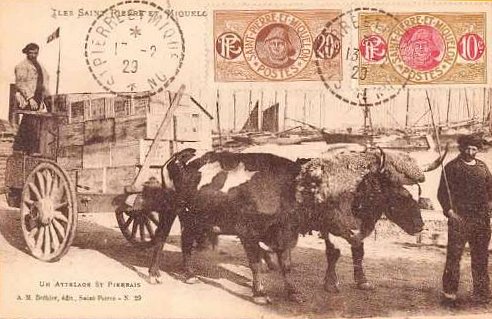

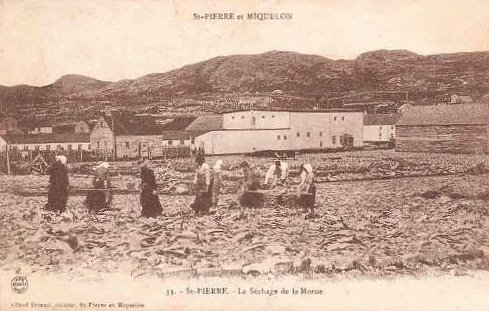

Although cod fishing on the Grand Banks was the main industry for centuries, this is an island that has known War, Deportation, Revolution and the spoils of Prohibition.

Beyond its history, Saint-Pierre et Miquelon is a wonderful destination because of its mild refreshing climate, its beautiful landscapes, the quality of the air and the warmth of its inhabitants.

Saint-Pierre is the commercial and administrative hub of the islands. With a population of 6500, the infrastructure is modern and urban.

The people of Saint-Pierre are descendants of Basque, Breton, Normand and other French regions.

According to recent archaeological discoveries, the islands were used a seasonal base for over 8000 years by many native peoples including the Beothuk and the Paleo Eskimo.

The European fishery on the Grand Banks began over 500 years ago when explorer Giovanni Caboto claimed all that was needed to harvest codfish was to lower a basket into the sea. The islands of Saint-Pierre et Miquelon were baptized the Eleven Thousand Virgins by Joao Alvarez Faguendes of Portugal in 1520, the Green Islands by the Corte Real brothers and the Island of Saint-Pierre by Jacques Cartier in 1536. By 1579, the island of Miquelon was given its name by Basque fishermen.

"Nous fumes ausdictes yles sainct Pierre, ou trouvasmes plusieurs navires, tant de France que de Bretaigne, depuis le jour sainct Bernabe, XIe de juing, jusques au XVIe jour dudict moys" - Jacques Cartier, June 1536.

The French Merchants of Saint-Malo settled in Saint-Pierre in the late XVIIth century and established a very large curing and salting operation for codfish. The tribulations of war between France and Britain would put an end to the French colonies in Placentia Newfoundland and Saint-Pierre et Miquelon and The treaty of Utrecht of 1713 forced Saint-Pierre's inhabitants into exile in Isle Royale (Cape Breton, Nova Scotia).

"The Island is as subject to Fogs as any part in Newfoundland yes if we may credit the late Planters it is very convienient for catching and curing of Codfish." - James Cook, 1763

The treaty of 1763 returned the islands of Saint-Pierre & Miquelon back to France, and despite the subsequent deportations of 1778 and 1793, the islands were once again returned to France in 1816.

"The French, it seems, are determined to lose no time in settling a colony at Miquelon and St Pierre." - the LONDON GAZETTE, June 5 1783

For the next hundred and eighty years, Saint-Pierre & Miquelon's main industry remained the Cod Fishery.

"St Pierre was once the liveliest fishing port in the world. The eighties of the last century beheld its greatest prosperity. In those days seven to eight thousand fisheman from St Malo, Fécamp, St Brieuc, and Dieppe, and the arrival of the Terre Neuves, the vessels and crews from France, was a wondrous, treasure producing event. The French and St Pierre armateurs, or outfitters, reaped golden harvests indeed." - Isles of Romance, George Allan England, 1929.

During both World Wars, the inhabitants of Saint-Pierre & Miquelon showed a very strong sense of sacrifice. Over a quarter of Saint-Pierre & Miquelon's conscripts died in World War I, and in World War II, the islands rallied De Gaulle's Free French in 1941.

Prohibition in the United-States caused a short lived period of prosperity and wealth for Saint-Pierre & Miquelon.

Today, the Fishing Industry is changing and adapting itself to new realities. A young and dynamic population is dedicated to ensuring the future of this French enclave in North America.

The history and development of St. Pierre and Miquelon have been tied to the dispersion of the French settlers from Acadie, in New Brunswick (the Acadians.)

The first Acadians to reach St. Pierre and Miquelon came from Cape Breton in 1758. After the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the Acadians were told that they had 18 months to relocate to French soil. The French govermnent recognized that St. Pierre and Miquelon would soon be faced with new settlers. In order to keep things under contral, they agreed to support only 300 Acadians. The new governor (Dangeac) and the 300 sailed from Rochefort on the Garonne and arrived in 1763. The governor also supplied the legitimate settlers with fishing equipment. But they were soon joined by others.

Since St. Pierre and Miquelon were the last French colonies left in North America after the treaty, hundreds of Acadians sailed there from Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New England. From 1763 to 1767, other Acadians came from French Atlantic cities. But the small islands didn’t have the resources to support them all, especially as farmers.

In October 1763, 116 Acadians arrived from Boston. They were followed in August of 1764, by 100 Acadians (from Cape Breton Island, Prince Edward Island, the Isthmus of Chignecto, and Chedabouctou) who had been imprisoned in Nova Scotian forts before sailing to Miquelon. In October of 1765, 111 Acadians from Prince Edward Island and Halifax also migrated to Miquelon. That same month, 72 Acadians from Beausejour made it to the islands. Acadians (about 50) on a French fishing fleet jumped ship at St. Pierre at about the same time.

Dangeac tried to get the new Acadian settlers to move to Guiana, but the tropical climate terrified the Acadians and they refused to go. They built meager homes, consisting of spruce stakes stuck in the ground and covered with sod. The chimneys were made of clay, mud, and hay. There wasn’t enough building materials to construct sturdy homes for everyone.

Finally, Dangeac had enough. When 72 Acadians arrived in November of 1765, he sent 43 of them to Nantes, France. He communicated the problem to France, and the unauthorized Acadian settlers were ordered to go to Acadia (Nova Scotia) or France. The didn’t want to return to Acadia. Some said they would go to Louisiana, but nothing became of it. Actually, 14 from this group eventually made it to Louisiana aboard the seven ships in 1785.

From October to December of 1767, 763 people (almost all Acadians) left the islands. Most (586) went to France, while the rest (163) went to Acadian (actually, to Cape Breton Island, Ile Madame, and Cocagne).

After the island population was drastically reduced, the merchants began to speak up ... saying how the island could support more if they engaged themselves in the fishing industry. So 240 Acadians at St. Malo and Rochefort asked the French government to reconsider their position. In 1768, Choiseul said okay, and allowed a limited number of them to return (if they were self-supporting and would pay their own transportion). Two Acadian schooners brought 103 Acadians back to the islands. The Creole sailed from Rochefort carrying 37 Acadians; it arrived at Miquelon on May 5, 1768. The Louise carried 66 more, arriving on June 23, 1768. Choiseul later agreed to transport them for free, and 219 more made the trip.

The Acadians tried to raise livestock, but it proved to be a failure. When the demand for codfish increased, they were able to improve their situation. By 1776, the population of St. Pierre and Miquelon was 1894.

Trouble returned in 1778, when France declared war on England. The Acadians on St. Pierre and Miquelon were herded onto ships as their settlements were destroyed. They were sent to France, where they lived on welfare in the port towns of St. Malo, La Rochelle, Cherbourg, Rochefort, and Nantes. After the peace treaty in 1783, 1250 Acadians asked to return to St. Pierre and Miquelon. In 1783, 510 Acadians returned to the islands, and 713 followed the next year.

The settlements were rebuilt, and the cod fishing industry was resumed. Acadians and Frenchmen from the continent even traveled there to work during the summers. But with success came yet another invasion. On May 14, 1793, a small British force raided the island and sent the small French garrison and non-resident fisherman to Halifax. From there, they were sent to France ... arriving in mid 1794.

The resident Acadian fisherman were told to work for the English, but they refused. So the English decided to expel all of them. But before they could, about 32 Acadian families left for Iles Madeleine (1793). More (360) Acadians sailed for Ile Madame. In September 1796, the remaining Acadians on the islands were sent to Halifax. They were placed in nearby fishing villages and forced to work on English fishing boats in the Grand Banks.

Finally, in July of 1796, the government said they could go to France. In July 1797, a number of them sailed to Bordeaux in France. The following month, more Acadians sailed to Le Havre.

When a treaty was made in 1814, hundreds of Acadians returned to St. Pierre and Miquelon. By 1820, there were 800 Acadians on the islands.

Saint-Pierre & Miquelon — is South of the Canadian province of Newfoundland, about 800 miles North East from Boston (see maps). An integral part of the French Republic, they are the last remnant of France’s once large possessions on this continent.

Today, both Saint-Pierre & Miquelon are modern, quaint French towns and the most original destination in all of North America.

Although Fishing Cod on the Grand Banks was the main industry for centuries, this is an island that has known War, Deportation, Revolution and the spoils of Prohibition.

Beyond its history, Saint-Pierre et Miquelon is a wonderful destination because of its mild refreshing climate, its beautiful landscapes, the quality of the air and the warmth of its inhabitants.

Saint-Pierre is the commercial and administrative hub of the islands. With a population of 6500, the infrastructure is modern and urban.

The people of Saint-Pierre are descendants of Basque, Breton, Normand and other French regions.

Ile aux Marins (Ile aux Chiens)

A small island situated across the harbour from Saint-Pierre, Ile aux Marins used to be a fishing village of 600 souls. Modern fishing techniques contributed to the gradual desertion of the community. Today, Ile aux Marins is a living museum and a unique window on our past.

Miquelon

On the northern side of this larger island, the village of Miquelon is inhabited by 600 people, mostly of Basque and Acadian ancestry.

Wildlife is most abundant on this island and its couterpart to the south, the island of Langlade. The 8 mile sand dune between the two islands is peppered with over 500 shipwrecks.

Langlade

South of Miquelon, Langlade is a very rugged yet beautiful island surrounded by steep cliffs. Several farms specialize in organic produce and livestock. Langlade is also a favorite summer residence for many islanders.

Other islands

There are many other islands around Saint-Pierre & Miquelon, they not easily accessible but many bird watchers and nature lovers sometimes manage to visit these untouched ecosystems like the Grand Colombier.

Other islands have been inhabited at one time or other, and they include

l'Ile aux Vainqueurs, l'Ile aux Pigeons and l'Ile Verte.